"

Understanding President Obama's Partisanship

As I wrote last week, a political party is an extra-governmental conspiracy to control the government. Partisans coordinate their efforts across branches to centralize power in a system that otherwise disperses it far and wide.

Partisanship is simply partiality to one conspiracy over another. It's a bias or an inclination. Partisans are more receptive to arguments from their own side than those proffered by the opposition. They are more apt to notice the malfeasances of those on the other side, while often ignoring the sins on their own side. They're willing to give their side credit, but are stingy when it comes to praising the other side. And so on.

For as much as partisan Democrats and Republicans disagree on policy - their views of the political process are often mirror images of one another. This is especially true when it comes to attitudes about the public discourse.

The public discourse is simply the national political conversation. Dominated by the two parties, it consists of partisan arguers who make partisan arguments. Partisan Democrats and Republicans often hold exactly opposite views on both. Let's examine each in turn.

First, regarding the arguers, what motivates them to be partisan?

There are two basic motivations. The first is a commitment to the party's public policy goals. This is the belief that one's own side has correct solutions to public problems, and the opposition has wrong ones. The other motivation is not as noble. To get people to sacrifice private profit, society has made work in representative government prestigious. This breeds private reasons for partisanship - something to the effect of, "I want to keep my awesome job. Those guys are trying to take it from me. So, to hell with them!"

It's fair to say that public and private interests have motivated officials on both sides in roughly equal measure. Yet Republicans and Democrats often act as though their side is vastly superior to the other. Republicans often see their members as representing their views fairly and accurately, but Democrats accuse Republicans of being pawns of the business interests. Democrats see their members as public-spirited; Republicans paint them as the tools of the labor unions.

Second, what kind of arguments are the partisans making?

Arguments can be rationally developed in an attempt to persuade a thoughtful public. On the other hand, they can make recourse to propaganda - one-sided, tendentious appeals, often to the passions rather than reason.

Reason and propaganda have comingled throughout the history of the American political debate. For instance, Federalist #10 is James Madison's reasoned disquisition on the value of a large republic. But in Federalists #6, 7, and 8 Alexander Hamilton sets the gold standard for partisan fear-mongering - warning that if the states do not unite under the Constitution, war will be followed by plunder, permanent armies, and even monarchy. Partisan discourse today often follows the example set by the Federalist Papers: a mix of cool rationality with heated propaganda as partisans try to persuade an undecided, uninformed, and indifferent public.

Yet here again, Democrats and Republicans often have exactly opposite views of who is using what type of argument. Partisan Republicans are inclined to dismiss Democratic assertions as the product of faulty data, specious reasoning, and an appeal to some set of base emotions. Meanwhile, they view their own arguments as derived from self-evident principles and grounded in the finest traditions of American history. Partisan Democrats, of course, see themselves as the keepers of the American faith, and the Republicans as the purveyors of propaganda.

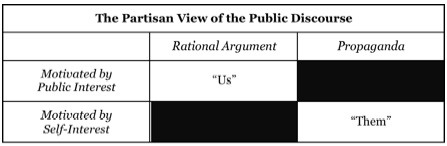

So, on both fronts - arguers and arguments - I would suggest that partisans have exactly opposite views. This enables us to generalize the partisan view of the public discourse into a simple chart:

Importantly, not all Republicans are "partisan Republicans" in this sense, nor are all Democrats "partisan Democrats." One can, at least in theory, hold Republican policy preferences without having these views about the two sides. Ditto if one is a Democrat. In practice, I think it is more accurate to say that at least some partisan bias is inevitable for those who pay close attention to or participate in politics, and that some subscribe less fully to the partisan worldview than others.

President Obama's introductory remarks to the House Republican caucus suggest that he holds a partisan Democrat's view of the public discourse. In that address he regularly cites his desire to turn down the partisan dials and the value of a robust debate, but he couches those gestures to bipartisanship in a very negative view of how the opposition has actually behaved.

The President begins with a broad, philosophical affirmation of the value of the partisan debate:

I'm a big believer not just in the value of a loyal opposition, but in its necessity. Having differences of opinion, having a real debate about matters of domestic policy and national security -- and that's not something that's only good for our country, it's absolutely essential. It's only through the process of disagreement and debate that bad ideas get tossed out and good ideas get refined and made better. And that kind of vigorous back and forth -- that imperfect but well-founded process, messy as it often is -- is at the heart of our democracy. That's what makes us the greatest nation in the world.

This is a heartening statement to hear from any President. Party politics is messy and unpleasant, but ultimately necessary for the good functioning of our democracy. The Election of 1800, for instance, was one of the ugliest in American history. Still, big ideas were discussed, and the country made an important decision. To borrow the title of a recent book on that election, American democracy is a "magnificent catastrophe."

During the subsequent question-and-answer session, the President returns to the value of spirited debate and indicates a hope that the two sides could have a productive dialogue.

But the President starts to lose me shortly thereafter. He says:

I want you to stand up for your beliefs, and knowing this caucus, I have no doubt that you will. I want us to have a constructive debate. The only thing I don't want -- and here I am listening to the American people, and I think they don't want either -- is for Washington to continue being so Washington-like. I know folks, when we're in town there, spend a lot of time reading the polls and looking at focus groups and interpreting which party has the upper hand in November and in 2012...

I'm still technically on board here. I agree that politicians are often out there playing "politics," working for their own self-interest rather than the public good. Yet he soon pivots from trumpeting the virtues of bipartisanship to initiating a partisan attack:

[W]e have a track record of working together. It is possible. But, as John, you mentioned, on some very big things, we've seen party-line votes that, I'm just going to be honest, were disappointing. Let's start with our efforts to jumpstart the economy last winter, when we were losing 700,000 jobs a month. Our financial system teetered on the brink of collapse and the threat of a second Great Depression loomed large. I didn't understand then, and I still don't understand, why we got opposition in this caucus for almost $300 billion in badly needed tax cuts for the American people, or COBRA coverage to help Americans who've lost jobs in this recession to keep the health insurance that they desperately needed, or opposition to putting Americans to work laying broadband and rebuilding roads and bridges and breaking ground on new construction projects.

That's a Democratic view of the public discourse. The President "honest(ly)" expresses "disappointment" at a lack of bipartisanship, which was absent because of inexplicable opposition from the Republican Party. In other words, the Republicans did not offer and have not yet offered valid reasons to oppose the stimulus bill.

Why did they oppose it? The temptation for self-interested political calculation was too great:

And let's face it, some of you have been at the ribbon-cuttings for some of these important projects in your communities. Now, I understand some of you had some philosophical differences perhaps on the just the concept of government spending, but, as I recall, opposition was declared before we had a chance to actually meet and exchange ideas.

The President makes a rhetorical nod to "some philosophical differences perhaps on the concept of government spending" (emphases mine) - but his point here is that bipartisanship has been absent because the Republican caucus has largely been acting out of its own political self-interest.

Interestingly, throughout the session, the President frequently makes use of a form of propaganda to justify this position. His reasoning often goes something like this: you Republicans supported particular items within these bills, so you should have supported the bills; that you did not is a sign that you've been playing politics, and your objections were not tenable. This is a fallacy of composition.

This is how he concludes his introductory remarks:

Bipartisanship -- not for its own sake but to solve problems -- that's what our constituents, the American people, need from us right now. All of us then have a choice to make. We have to choose whether we're going to be politicians first or partners for progress; whether we're going to put success at the polls ahead of the lasting success we can achieve together for America. Just think about it for a while. We don't have to put it up for a vote today.Let me close by saying this. I was not elected by Democrats or Republicans, but by the American people. That's especially true because the fastest growing group of Americans are independents. That should tell us both something. I'm ready and eager to work with anyone who is willing to proceed in a spirit of goodwill. But understand, if we can't break free from partisan gridlock, if we can't move past a politics of "no," if resistance supplants constructive debate, I still have to meet my responsibilities as President. I've got to act for the greater good -- because that, too, is a commitment that I have made. And that's -- that, too, is what the American people sent me to Washington to do.

His question-and-answer session basically follows the same script. He combines broad appeals for rigorous debate and cooperation with not-so-subtle attacks on Republicans for not participating in a serious manner. It seems that the President's view is that the Republicans are putting "success at the polls ahead of the lasting success we can achieve together for America" and offering irrational arguments that the President "(didn't) understand then, and...still (doesn't) understand" today.

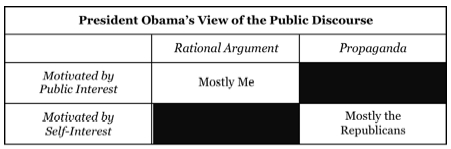

To return to the previous chart, his introductory remarks suggest that this is how the President views the public discourse:

Since he was inaugurated, I have been critical of President Obama's failure to live up to his pledge of bipartisanship. But maybe he has lived up to it, at least on his own terms.

After all, the line of reasoning in this essay suggests a partisan view of bipartisanship, which would go something like this:

We're the ones who are (mostly) public-spirited and rational; they're the ones who are (mostly) self-interested and using propaganda. Thus, bipartisanship will come when they mend their ways.

In so doing, they will start to agree with us. While there may be some lingering divisions, many will disappear. After all, if both sides are motivated by the public interest and making recourse only to rational argument - how much divergence can there possibly be?

This could reconcile Obama's complaints about what he saw as mere gestures from the previous administration with his belief that congressional Republicans should have been happy with the gestures he made to them. This partisan view of bipartisanship doesn't suggest a meeting at the halfway point. The meeting point depends on which party is more virtuous and more reasonable. If the President thinks he has the market cornered on both assets, then the idea that Bush should have given more is quite compatible with the thought that he has given enough.

"

============================It is truly a pleasure to read Jay Cost's blogs!!